By Dr Dyfan Powell, Wavehill

This is another blog in a series of three, which will explore the relationship between specific sectors of the economy and the Welsh language in Gwynedd. The tourism industry is the subject of this blog, a sector which has stirred interesting debates recently, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis.

Twenty years ago, research by Dylan Phillips shed light on employment growth in the tourism sector and the thousands that were employed in the industry by the end of the 1990s.[1] The article raised questions regarding the cost and long term impact of employment in such a sector in the area, and provided evidence linking tourism and in-migration. He looked at studies which found that half the people who had moved to areas such as Llandudno had previously visited the area as tourists,[2] while 59% of summer/holiday home owners intended to retire to the area.[3] That is to say, although tourism creates jobs in the short term, those who had visited on holiday were buying second homes or intended to retire in the area later in life.

The general assumption is that this pattern is ongoing. However, although people are employed in the sector in the short term, there is very little statistical data regarding the impact of the tourism industry on the language, while the long-term implications are still deemed to be detrimental to the language by encouraging in-migration by non-Welsh speakers, in turn exacerbating challenges regarding the affordability of houses.

As part of Wavehill and JP Consulting’s research work, the sector’s employment data and its relationship with the Welsh language was explored. The conclusions are interesting, but complicate our understanding of the link between the tourism sector and the language in Gwynedd.

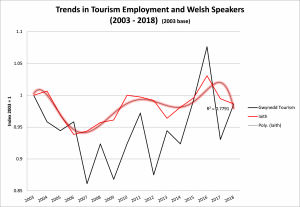

It’s possible to extract data from 1960-2018, but the relationship is not significant over this period. But while scrutinising recent data, especially from 2003-2018, the relationship becomes stronger, and we see a significant and positive relationship i.e. as the sector’s employment increases, the numbers of Welsh speakers increase. The data for the latest period is shown in the table below.

The data therefore suggests that, historically, there has not been a strong relationship between the tourism sector and the language. But more recently, especially during the last twenty years, there has been a relationship between employment in the sector and the language’s growth and sustainability. It is a positive relationship, which suggests that the employment within the sector has supported the language.

This is only a statistical relationship, and more research and data will be needed to enhance the understanding of this relationship, but it is possible to suggest a theory to explain it. The data is in keeping with the presumption that the industry enables local people, in this case Welsh speakers, to live and work in the area. The sector is therefore important, and employment in the sector has a direct impact on the language which is more positive than, for example, the agriculture sector.

But before leaping to try and expand employment in the sector, some important points need to be stated. The wages tend to be low on average, especially for seasonal workers. The COVID-19 crisis has also emphasised how insecure these jobs are.[1] But turning to the language, there is no data to suggest that Phillips’s argument isn’t still valid today and the long term impact of the tourism industry should be considered on migration patterns and house prices – two important factors as regards the viability of the language.

The sector is therefore complicated, as it brings short term benefits but is very possibly detrimental to the language in the long term. The sector’s employment is high in Gwynedd, and the jobs allow Welsh speakers to live and work in the area. But the industry attracts migrants who generally don’t speak welsh and who buy houses at prices that are largely unaffordable to local people.

[1] Phillips, D. (2000). ‘We’ll keep a welcome? The effects of tourism on the Welsh language’, in Jenkins, G.H. and Williams, M.A. (edited) Let’s Do Our Best for the Ancient Tongue – The Welsh Language in the Twentieth Century. Reprinted, Wiltshire: CPI Antony Rowe, 2015, page. 527-550.

[2] Law, C.M. a Warnes A.M. (1973). ‘The movement of retired people to seaside resorts: A Study of Morecambe and Llandudno’, The Town Planning Review, Vol. 44, No. 4 (Oct. 1973), page. 373-390. Not available for this Review.

[3] Pyne, C.B. (1973). Second homes. Caernarfon County Planning Department.

[4] https://www.dailypost.co.uk/news/north-wales-news/figures-show-how-many-workers-18601928